Brecht's Epic Theatre

Some extracts from 'The Street Scene - A Basic Model for an Epic Theatre' by Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Willet, with annotations and commentary relating to our project.

the point is that the demonstrator acts the behaviour of driver or victim or both in such a way that the bystanders are able to form an opinion about the accident.

Finding ourselves in such a tourist city as Athens, we wanted to avoid presenting people with something they simply consume and take pictures of and say 'oh that was nice'

The demonstrator need not be an artist. The capacities he needs to achieve his aim are in effect universal.

We worked quickly, with whichever collaborators turned up. The intention was more important than any supposed technique. This is in opposition to most clown training in Europe today, so influenced by Lecoq and Gaulier.

Suppose he cannot carry out some particular movement as quickly as the victim he is imitating; all he need do is to explain that he moves three times as fast, and the demonstration neither suffers in essentials nor loses its point.

We wanted to join physical actions, visual impact and speaking directly with onlookers, in Greek or English. Speaking is one of our most direct ways to inter-personal communication. Again, this contradicts the Lecoq orthodoxy which emphasises the embodied actor.

On the contrary it is important that he should not be too perfect. His demonstration would be spoilt if the bystanders’ attention were drawn to his powers of transformation. He has to avoid presenting himself in such a way that someone calls out ’What a lifelike portrayal of a chauffeur!’ He must not ’cast a spell’ over anyone. He should not transport people from normality to ’higher realms’. He need not dispose of any special powers of suggestion.

This may come to be more important as we explore further what we mean by 'ritual'.

It is most important that one of the main features of the ordinary theatre should be excluded from our street scene: the engendering of illusion. The street demonstrator’s performance is essentially repetitive.

In the festive tradition, performances are often repeated in different parts of the town or village.

The demonstration would become no less valid if he did not reproduce the fear caused by the accident; on the contrary it would lose validity if he did. He is not interested in creating pure emotions.

On the other hand, we WERE interested in some eliciting of real emotion, to draw onlookers into empathy with the fate of the eggs. Though we did not yet reach this point in our process.

One essential element of the street scene must also be present in the theatrical scene if this is to qualify as epic, namely that the demonstration should have a socially practical significance. Whether our street demonstrator is out to show that one attitude on the part of driver or pedestrian makes an accident inevitable where another would not, or whether he is demonstrating with a view to fixing the responsibility, his demonstration has a practical purpose, intervenes socially.

Our own 'subject matter' socially speaking was initially the issue of migration to Europe, the crossing of boundaries, and the global disaster of war. Eventually, addressing these questions is the point of our research, not the creating of a new aesthetic, nor the discovery of what clowning is.

Another essential element in the street scene is that the demonstrator should derive his characters entirely from their actions. He imitates their actions and so allows conclusions to be drawn about them.

Hence our interets in ritual, or repeated actions, perhaps meshed with work actions, the rhythms and gestures of labour.

Next-door neighbour and street demonstrator can reproduce their subject’s ’sensible’ or his ’senseless’ behaviour alike, by submitting it for an opinion.

The onlookers will always have an opinion, but can we validate it and foreground it?

We have to find a point of view for our demonstrator that allows him to submit this excitement to criticism.

The theatre’s demonstrator, the actor, must apply a technique which will let him reproduce the tone of the subject demonstrated with a certain reserve, with detachment (so that the spectator can say: ’He’s getting excited—in vain, too late, at last. . . . ’ etc.). In short, the actor must remain a demonstrator; he must present the person demonstrated as a stranger, he must not suppress the ’he did that, he said that’ element in his performance. He must not go so far as to be wholly transformed into the person demonstrated.

Also relevant to how we create ritual. What part does ecstasy play?

He never forgets nor does he allow it to be forgotten, that he is not the subject but the demonstrator.

A valuable antidote to the school of thought that assumes that clowning is deep, personal and necessarily a route to your own fun.

We now come to one of those elements that are peculiar to the epic theatre, the so-called A-effect (alienation effect). What is involved here is, briefly, a technique of taking the human social incidents to be portrayed and labelling them as something striking, something that calls for explanation, is not to be taken for granted, not just natural.

Reminder that Brecht's ideas about acting were derived from clowns: Chaplin and Karl Valentin.

The demonstrator achieves it by paying exact attention this time to his movements, executing them carefully, probably in slow motion; in this way he alienates the little sub-incident, emphasizes its importance, makes it worthy of notice.

See Brecht's notes on Chaplin.

The model [of epic theatre] works without any need of programmatic theatrical phrases like ’the urge to self-expression’, ’making a part one’s own’, ’spiritual experience’, ’the play instinct’, ’the story-teller’s art’, etc.

See above note on clown orthodoxy.

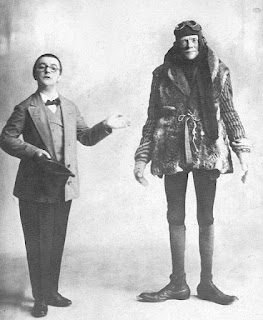

There must be no question of creating an illusion that the demonstrators really are these characters. (The epic theatre can counteract this illusion by especially exaggerated costume or by garments that are somehow marked out as objects for display.)

See our use of costume which is at once familiar and other-worldly.

Our street corner theatre is primitive; origins, aims and methods of its performance are close to home. But there is no doubt that it is a meaningful phenomenon with a clear social function that dominates all its elements. The performance’s origins lie in an incident that can be judged one way or another, that may repeat itself in different forms and is not finished but is bound to have consequences, so that this judgment has some significance. The object of the performance is to make it easier to give an opinion on the incident. Its means correspond to that.

As producer and actors work to build up a performance involving many difficult questions—technical problems, social ones—it allows them to check whether the social function of the whole apparatus is still clearly intact.

A reminder to constantly check whether we are on track with our basic aims, and not to be drawn into the temptations of the qualities of performance.

[’Die Strassenszene, Grundmodell eines epischen Theaters’, from Versuche 10, 1950]

NOTE: Originally stated to have been written in 1940, but now ascribed by Werner Hecht to June 1938. This is an elaboration of a poem ’¨Uber allt¨agliches Theater’ which is supposed to have been written in 193o and is included as one of the ’Gedichte aus dem Messingkauf’ in Theaterarbelt, Versuche 14 and Gedichte 3. The notion of the man at the street-corner miming an accident is already developed at length there, and it also occurs in the following undated scheme (Schriften zum Theater 4, pp. 51–2):

Comments

Post a Comment