Final Day Assessments

On our last day together in Athens, the three of us revisited the project and reflected on:

- 2 days collaborating with others

- the whole project and the lessons we can draw

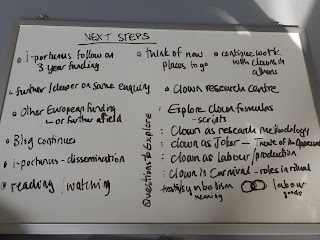

- what we want to do next

Group cohesion and complicity

Compared to the first day, the second day with collaborators brought a higher level of cohesion and group complicity. This probably arose from having a group organization, with tasks assigned from the beginning of Day 2, as opposed to Day 1 when each individual could set their own tasks. Particularly on the return to the workspace, there was much more group work than on the journey from the workspace to the designated place of action on Day 2.

However, valorising this is not an easy task. Some collaborators, in the feedback, valued the individual freedom of Day 1 over the group cohesion of Day 2. The feedback of others was the opposite. In general, this valorisation was related to the fun that the person reported having.

This raises another question: how is the success of the project measured? Is 'having fun' an important variable? We discussed, as researchers, whether this has a positive or negative impact on our research aims. Does the attraction of having fun work for or against our broader goals (articulated as creating the conditions in a public space for viewers to validate their own questioning and become so-called 'spectators')? Indeed, does the attraction of group complicity work for or against these ends? Between the three researchers, our initial feelings covered a spectrum. We agreed that we would like to explore these questions in more detail in the future. This would involve, for example, observing whether the structure of multiple roles (internal actors, intermediaries, spectators, etc.) is better served or not.

These questions arose not only from the feedback of collaborators, but also from our own perceptions and experiences during the Day 2 event. The three of us agreed that the outward route was very different from the return route. However, we had different valorisations of that difference. Did these perceptions depend on our own clown roles within the event? For example, I (Jon) felt that the outward route had more variety, room for interaction, and contrast. But, as one of the solo clowns in charge of interacting with onlookers, was it just a perception that I had 'more to do'? While on the way back I had 'less room to do things', I perceived that the group had taken on the roles of central actors and interacting with the onlookers. In contrast, was Robyn's perception as the leader of the group the opposite of mine because she found 'more to do' on the return route?

What seemed easier to identify were the reasons for the change. The group clowns, at the event place, engaged in more activity (as planned) than on their outward route. When they returned, they were more 'warmed-up', daring and playful than on their way out.

Ritual Actions

In some of the feedback from collaborators, the term 'tribal' was used to describe some of the qualities of the group actions. Considering this term problematic, as researchers we discussed where this perception might have emerged from, and what we might have been doing to elicit such a response. This discussion led to an agreement that we would like to explore more in detail in the future what we wanted the group actions to be. We acknowledged that the term 'ritual' had begun to be used by us at some point, and that we would like to interrogate ourselves on what we meant by that, or whether we wanted to continue using such a concept.

The actions planned and carried out on Day 2 by the group had been devised and agreed in a very short space of time. As such, swift methods had been necessary in order to create agreed actions. These included such ensemble techniques as flocking, following the leader, sound-gesture intensification, etc. In the week preceding the street actions, we had discussed many possible actions that could be done using eggs - painting faces, breaking, throwing, putting in boxes, rolling, catching, hiding, using blown eggs, etc. We didn't have time to incorporate much of this into our actions, apart from the throwing of eggs at the end.

We agreed that we would like to explore in detail in the future how we could stage these actions. Are these actions of everyday labour? What happens when they are combined in unexpected, but familiar ways? And how does this contrast with the group work on 'ecstatic' togetherness that we did on Day 2? Can we combine these two modes? What purpose do the modes serve?

We felt that a rigorous appraisal of these questions will be needed in order to avoid simplistic reproduction of clichés of the other as 'primitive, tribal or savage'.

This questioning seems focused on the same objective: how to create the conditions for the spectactor? How do the distinct roles work? What is the relationship between mask/unmasked, civic/wild, human/mythical, clown/trickster, ecstasy/labour, eye-contact/no-eye-contact, in-costume/out-of-costume?

Quick Quick Slow - a Research Methodology

Looking back over the rhythm of the project, we perceived the following patterns:

A slow, five-day period gathering ideas, brainstorming, elaborating on images and actions, exploring our clown roles, reflecting on our clown lineages.

A quick process of presenting materials and aims to a group, going swiftly from costume-making to street-action. Following the actions, there were multiple questions, thoughts, discoveries.

The need for a new slow period next, for us to work in more detail on the outcomes. Probably to be followed by more quick processes to test out new hypotheses.

This methodology we characterised as Quick-Quick-Slow, where work is done to prepare experiments, which then give rise to multiple new data, that must then be processed in detail. We consider this to be an appropriate clown methodology and one which parallels the scientific method.

This has clear implications for when we work with collaborators. Instead of inviting people to do what they want, or to find what is fun for them, which could lead only to reproducing what all of us already know, we propose to offer collaborators certain tasks, or scripts, which elicit new and unexpected outcomes. We would also apply this to ourselves as researchers, evidently.

Comments

Post a Comment